This week I have started documenting our target architecture. Now, what I was actually asked to do was “document our target cloud infrastructure”, but I have been there before and believe a formal (ish) overall architecture description is required before diving into any specific problem area.

I am going to use this post to describe how I use architecture descriptions and other architecture modelling techniques. I do not claim this is the only way or even the right way, but it works for me so might work for you as well.

Architecture description

What do I mean by an architecture description? I mean Systems and software engineering — Architecture description ISO/IEC/IEEE 42010 which is an old fashion standard I was once required to adhere to for a government project.

Now, in those waterfall days, my role as software architect was to design the solution upfront before delivering a formal, all encompassing description of it to the development teams. At the time it was easy, and a good idea, to use the viewpoints and perspectives listed in Rozanski and Woods “Software Systems Architecture”(R&W) book. In particular the book (but sadly not the website) helped me examine my architecture through different angles and lenses, and provided a lot of checklists to validate both the solution and my description of it.

Today, with lean and agile development processes adopted wholesale throughout the industry, I can be an agile architect, and never again create such a big design up front.

I am however still a big fan of ‘proper’ architecture supported by appropriate descriptions, which often puts me at odd with the Agile (with a big A) crowd who misunderstand “Working software over comprehensive documentation” as meaning “no documentation”. I, personally, have found that the tools and techniques used to put an architecture descriptions are essential to support the conversations and eventual decisions that we take as a team, and to convey these decisions at various level of the organisation (what Gregor Hohpe calls “riding the architect elevator to connect the penthouse with the engine room”). My architecture descriptions now pick and choose from a multitude of modelling techniques, whatever works to best communicate a particular aspect of the solution to my stakeholders.

Format

As much as I love a good diagram, I make a point to use both text and diagrams, the rule being that any important information appearing in the latter will be reflected in the former - that is I never rely solely on visual information. Vice-versa, I can be quite verbose so always try to reflect what I write in supporting diagrams. The added advantages of doing so are threefold:

- the act of comparing text and diagram forces me to see both through the eye of my stakeholders, and identify incongruences.

- iterating between text and diagram, adding or removing information from one to better align with the other generally improves the content, usually by simplifying it.

- I get a ready made powerpoint slide - show the picture on screen and use the text as my spiel.

I have tons of books on the Unified Modelling Language (UML) and have used it extensively in my career, and know for a fact that most people don’t care for it, don’t understand it and find it ugly. And to be fair, they are mostly right.

When documenting a cloud architecture, it is preferable to use the prettier, and now ubiquitous cloud architecture format (square icons, boxes and lines) to describe the technical elements. Where I need to include more normative information, I do still use UML, but limit myself to component and sequence diagrams, which are relatively accessible. For interactions I sometime use extremely parred down activity diagrams but find that business stakeholders prefer the Business Process Modelling Notation (BPMN).

Finally, for logical views, I give myself more artistic licence, and use whatever shapes and colours I need to describe any specific concept.

What is essential however is consistency between diagrams across the whole architecture description.

Granularity

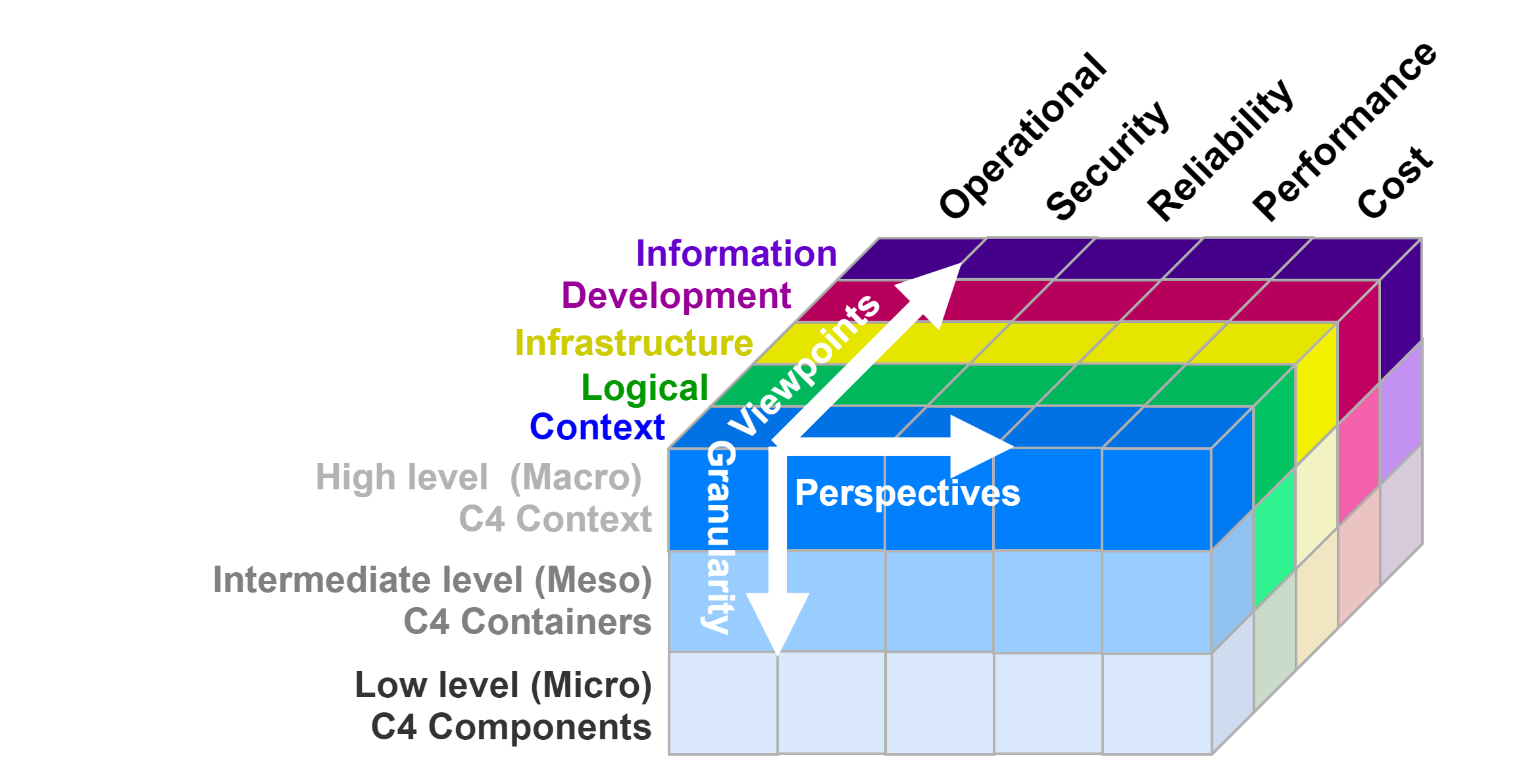

The architecture description provides 3 increasing levels of details, roughly aligned with C4 Modelling techniques, to support communication with a wide range of stakeholders, not all of which have an understanding of our technological or business domain.

The high-level (macro) view will consider the elements of the solution that are our responsibility, and how these elements relate to the wider architecture of the enterprise. It very much aligns with the notion of Context in C4 modelling, and as such supports conversations with non technical stakeholders outside our team, as well as colleagues having only just joined us.

The intermediate (meso) view will consider the major elements of our solution, and how they relate to each other, which aligns it with the C4 Container diagram, and support conversations with non technical stakeholders within our team or outside it but aligned to our business domain. Intermediate views are also a good basis to start technical conversations, or to reproduce ad-hoc on a physical or electronic whiteboard.

The detailed (micro) view will consider architectural and design patterns used to implement specific aspects of our solution, very much like C4 Component diagram. Detailed views can be used to support decision making at team level (aka detailed design) as well as more formal process gates such as Technical Design Authority reviews or change control management.

It is important however to note that the detailled design artefacts are not themselves part of the architecture description, but refer to the patterns and guidelines documented within it.

Viewpoints

Viewpoints are an ISO/IEC/IEEE 42010 - Systems and software engineering — Architecture description archetype. There are and have been a multitude of so-called view models in our industry, but my favourite is the approach described by Rozanski and Woods (R&W) by in their book “Software System Architecture”, which I have adapted with a set of viewpoint better aligned (imo) with agile and cloud architecture.

Context viewpoint

The context viewpoint was apparently a late addition by R&W to the second edition of their book, but is one I believe is essential to provide a solid foundation to architectural discussions and decisions.

They define it as:

The Context view of a system defines the relationships, dependencies, and interactions between the system and its environment—the people, systems, and external entities with which it interacts. It defines what the system does and does not do; where the boundaries are between it and the outside world; and how the system interacts with other systems, organizations, and people across these boundaries.

this is your zoomed out view showing a big picture of the system landscape. The focus should be on people (actors, roles, personas, etc) and software systems rather than technologies, protocols and other low-level details. It’s the sort of diagram that you could show to non-technical people.

Functional viewpoint

R&W define it as:

The view documents the system’s functional structure-including the key functional elements, their responsibilities, the interfaces they expose, and the interactions between them. Taken together, this demonstrates how the system will perform the functions required of it.

whereas the 4+1 model calls it the ‘logical view’:

The logical architecture primarily supports the functional requirements—what the system should provide in terms of services to its users. The system is decomposed into a set of key abstractions, taken (mostly) from the problem domain, in the form of objects or object classes. They exploit the principles of abstraction, encapsulation, and inheritance. This decomposition is not only for the sake of functional analysis, but also serves to identify common mechanisms and design elements across the various parts of the system.

A key word in the 4+1 definition is abstractions: the principal role of the functional viewpoints for is to name things. This is where we introduce the vocabulary that will be reused throughout the architecture description, its ubiquitous language (a term originating from Domain Driven Design), the rule of which is “a single name for each thing, and only one thing identified by any given name” (my clunky wording). We must give ourselves a vocabulary precise enough to support architecture discussions and decisions without having to constantly explain what we mean. And this vocabulary must abstract lower level implementation details, to stop these discussions getting bogged down.

When drawn, the functional view will make heavy use of non-descript boxes and arrows, ideal for electronic and physical whiteboarding sessions.

Infrastructure viewpoint

This is my preferred term over R&W ‘deployment’ and 4+1 ‘physical’ viewpoints. This is where we start naming technologies and drawing cloud diagrams. What is important here is to maintain traceability between abstractions (things we described in our logical views) and their physical implementation. This will stop us from suffering from the common disconnect between the fluffy abstraction and the nitty gritty of their implementation that has given both architecture and infrastructure such a bad name.

From an architecture description point of view, we must also refrain from describing every nut and bolt of our infrastructure, as there is no value in doing so. What we describe here as the elements that personify our architecture decisions, with just enough detail to explain how they do so, and no more.

Development viewpoint

Most view models have a development view, but mean different things by it. 4+1 describes it as:

[…] related to the ease of development, software management, reuse or commonality, and to the constraints imposed by the toolset, or the programming language

[…] include code structure and dependencies, build and configuration management of deliverables, system-wide design constraints, and system-wide standards to ensure technical integrity. It is the role of the Development view to address these aspects of the system development process.

In our architecture description it will be used to bridge the gap between the what - as documented in the Logical and Infrastructure views - and the how, that is how we as a tribe go from wanting a thing to have that thing up and running in production. We will document where architecture decisions are constrained by our software development lifecycle (SDLC) and vice-versa. For example our choice of development language might limit our choice of infrastructure components or design patterns. The way we organise ourselves, our teams topologies, might impact how we assign responsibilities to specific software and/or infrastructure components. Our agile development processes and our adoption of DevOps and DevSecOps practices will also influence our architecture.

Information viewpoint

This viewpoint is again inspired from R&W:

[…] high-level view of static information structure and dynamic information flow, with the objective of answering the big questions around ownership, latency, references, and so forth

Here we adapt and extend it to cover description of our data model, how and what information flows through our systems and, how and where it is stored and accessed from and who by.

This will support our Domain Driven Design, the definition or our interfaces, as well as threat modelling and compliance with the likes of General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards (PCI DSS).

Perspectives

These are a concept introduced by R&W and provide an elegant mechanism to address the non-functional attributes, also known as the quality attributes, or ‘-ities’ (security, availability, usability…). Rather than consider these concerns on their own, and risk being disconnected from the realities of our architecture, we acknowledge they are cross-cutting through the viewpoints described above.

This also enables us to use checklists to reassure ourselves our architecture description doesn’t have any blind spots. These checklists can (and should) also be used outside the architecture description as part of or day to day design activities, such as 3 amigo sessions, or even work items’ definition of ready.

Unfortunately, R&W Perspective catalogue does not map very well (imo) to a modern cloud based architecture. We will instead align our architecture description with the five pillars of well architected cloud solutions (e.g. AWS, Azure and GCP):

Operational perspective

We must ensure that our architecture supports our ability to develop, deploy, run and support the solution and its individual components. This perspective allows us to question the element described in any given viewpoint against this criteria.

Interestingly, R&W treated Operational attributes via a viewpoint of its own rather than a perspective, but with DevOps, that aspect in my mind is subsummed in the Development viewpoint.

AWS Well-Architected Framework Operational Excellence Pillar whitepaper is an essential read to understand operational attributes of our architecture.

Security perspective

Here we consider whether the elements described by a given viewpoint impact:

-

security - how we prevent unauthorized access to organizational assets such as computers, networks, and data, and maintain the confidentiality, integrity and accessibility (so called CIA triad) sensitive and/or business critical information.

-

privacy - how we control access to Personally Identifiable Information (PII) and other sensitive information and how it is used.

-

compliance - how we meet legal and regulatory requirements such as GDPR and PCI.

See also AWS Well-Architected Framework Security Pillar whitepaper.

Reliability perspective

This perspective validates that the elements described by a given viewpoint support our ability to perform correctly and consistently, and recover from failure inside or outside our control, at any scale.

See also AWS Well-Architected Framework Reliability Pillar whitepaper.

Performance perspective

Here we consider how the elements described by a given viewpoint support our ability to perform consistently and efficiently regardless of the demand placed on our systems by their users. Cloud infrastructure offers elasticity, i.e. can scale in and out on demand, which must be taken into account when architecting our solution.

See also AWS Well-Architected Framework Performance Efficiency Pillar whitepaper.

Cost perspective

Cloud infrastructure, and the ability to consume solutions ‘as a Service’ require us to have a clear understanding of the cost implications of our architecture decisions. The choice of components and patterns will greatly affect the overall cost of our solution, as well as the individual cost per-click/transaction. This must be considered as early as possible and become a first class concern in our decision process, weighed equally against sexier technical concerns.

See also AWS Well-Architected Framework Cost Optimization Pillar whitepaper.

Summary

Rather than a big monolithic amorphous chunk of documentation, architecture descriptions can be sliced and diced over 3 axes, with each cell hopefully supporting discussion and decision making within and without our team.

I will hopefully revisit the subject in later posts, notably to document my checklists and how and where I use them.